There was an unintended display of fireworks at the July 13th Zoom meeting of the New Bedford School Committee.

Christopher Cotter, Vice Chair of the Committee and a New Bedford Police officer, lectured two of his colleagues about the true nature of “School Resource Officers” ( SROs) — otherwise known as school cops: “Shame on you,” Cotter scolded Committee members Joshua Amaral and Colleen Dawicki, for suggesting there are still a lot of questions about the SRO program.

“You sit there and say that you don’t know what the program is, what it entails, whatever the case is, you have somebody sitting at your table as a School Committee member who has that knowledge. Shame on you for not asking first hand when or if you even had a question beforehand. […] The one thing that really irks me is that the hidden underlying statement here is that the SRO (School Resource Officer) program is a racist organization and part of white supremacy. […] Let me be the first to tell you, I am not a racist, I never have been a racist. I am a police officer. I am a human being.”

Officer Cotter’s rant was all because fellow members of the School Committee did not blindly accept his subjective views on the SRO program. Cotter also failed to recuse himself on the issue because of his professional relationship with the police.

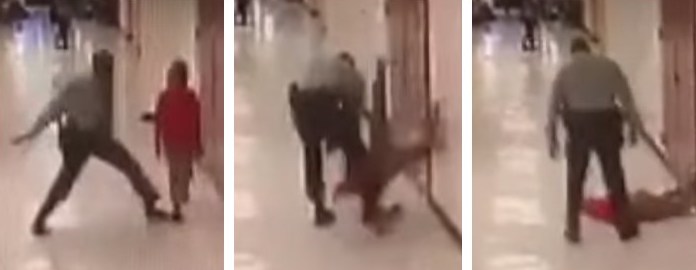

Nationwide, there are at least 20,000 school cops and roughly 42% of all school districts have one. There is even a professional association, NASRO, the National Association of School Resource Officers. Police claim SROs stop school shootings, but that was small comfort to Parkland, Florida students when their “school resource officer” refused to enter the school during a mass shooting. For the most part, school cops enforce school regulations, carry out discipline, recommend expulsions, and play their part — just like it sounds — in the school-to-prison pipeline.

In Education Under Arrest: The Case Against Police in Schools, the Justice Policy Institute (JPI) reports that “the allocation of $68 million through the Community Oriented Policing Services in Schools Program resulted in a 45 percent increase in the number of SROs between 1997 and 2000. These funds should have been used to support students and teachers in creating a healthy learning environment, rather than having been spent on placing law enforcement in our schools.” In June 2020, JPI called for removing all cops from K-12 campuses.

JPI Executive Director Marc Schindler noted, “Too often, issues that were once dealt with in the principal’s office are now dealt with in a police precinct, especially for youth of color. It is critical that we disrupt the school-to-prison pipeline. To do that we must remove police from our schools and reinvest those funds in staff and programs that are more likely to actually make schools safe and support our children as they grow and learn.”

According to JPI, roughly 1.6 million students nationwide attend a school with a law enforcement officer on staff, but not one school counselor! And Black students are 3 times more likely to attend a school with cops than mental health professionals.

At the virtual School Committee meeting, Cynthia Roy, co-chair of the New Bedford Coalition to Save Our Schools, let the School Committee know her mind: “The demand to remove police from schools and invest in restorative services is a reasonable way to validate the experiences of Black youth and demonstrate a commitment to racial justice. Quite frankly, it should be a no-brainer for New Bedford leadership to take up. […] The counterargument to keep police in schools is weak and grounded in prejudice.”

Likewise, New Bedford resident Cara Busch called SROs “one of many pillars of institutional racism in the United States,” adding, “They criminalize Black children and must be removed immediately from New Bedford Public Schools. […] It is not enough to say Black lives matter, we have to mean it, we have to do it, and we have to do it now. […] Depolicing New Bedford Public Schools is the lowest of low hanging anti-racism fruit.”

New Bedford Black Lives Matter organizers Shakira Duarte, Lynea Gilreath and Monique Onuoha wrote letters to the School Committee demanding that the District stop using “resource officers.”

The NAACP New Bedford Branch agrees. For years the Branch has advocated for educational equity and the removal of educational barriers for students of color. Police don’t belong in educational institutions unless they are investigating a crime. And we agree with JPI, BLM, NBCSOS and others — we ought to be spending municipal dollars on education, not police.

Unfortunately, In Massachusetts SROs are mandated by law in every school district. The “Reform, Shift + Build Act” (S.2820) which will shortly be considered by the Massachusetts Legislature makes SROs semi-optional but still not a matter for communities themselves to decide. The SRO provisions in the bill are an improvement over current law, but just barely.

SROs require an MOU (memorandum of understanding) between the Police Chief and the Superintendent. The law also requires that SROs be subject to an appropriations (budgeting) process. SROs are to be chosen based on “specialized training” and “requisite personality and character” traits. A lot of these requirements are documented in the MOU, which also contains descriptions of how information can be shared between schools and the police.

But the issue of SROs seems to be yet another battle in America’s culture wars. In 2010 the New Bedford City Council asked for an SRO in every elementary school.

By law SROs are not supposed to function as disciplinarians, but we have heard reports to the contrary. In addition, not all school personnel have a clear understanding of SRO legal restrictions and may ask them to perform duties outside their scope. A major function of SROs (according to Massachusetts statute, at least) is diverting at-risk youth into social programs. But how exactly does this work? And why are police doing this instead of guidance counselors? It seems analogous to locking people up and giving sheriffs the job of treating their drug dependency and mental illness instead of providing them with competent, professional, care on the “outside.” Wrong people, wrong institutions.

Last June, the New Bedford Coalition to Save Our Schools (NBCSOS) hosted a forum on SROs followed by a question and answer period. The forum hosted a number of educational experts, including Dr. Erica R. Meiners, Dr. David Stovall, and Dr. Aaron Kupchik, professor of sociology and criminal justice at the University of Delaware, who provided evidence that the harms of putting cops in schools outweigh the benefits to students, particularly students of color. “The research is clear that school safety is not improved with the use of permanent SROs. In fact, many feel unsafe in the presence of police officers. This is a local, statewide, and national problem,” NBCOS wrote.

Also participating was NAACP New Bedford Branch president, Dr. LaSella Hall, who called for SROs to be immediately removed from schools. Certified school counselors and therapists with racial sensitivity and implicit bias training, who understand what it means to work with the populations they serve, should be hired instead, Dr. Hall said. And these ideas aren’t all that new, he emphasized.

The NAACP made its position on SROs crystal clear in a 2018 resolution submitted by the Fairfax, Virginia branch: “BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED that local NAACP units advocate that police/security officers should not work in or be found in schools.”

The NAACP encourages local branches to investigate SRO programs in their own communities or to take action to remove them. In Beloit, Wisconsin, for example, the NAACP branch demanded information on suspensions, expulsions and referrals from “school resource officers.” In Boulder, Colorado, the local branch called for the removal of SROs. In Fairfax, Virginia, the NAACP called for the state to stop funding them. In Duluth, Minnesota the NAACP branch co-signed a petition for the removal of SROs.

So let’s not just take Officer Cotter’s word for it. Let’s look at the data. By race, for all incidents, referrals to social services, detentions and other discipline, expulsions, and arrests. Let’s look at the details of the District’s MOU with the police and review MOU-related correspondence between the Schools and the Police. And let’s look at the metrics the New Bedford Schools use to define what “success” of an SRO program looks like to them.

But to us, success is providing real resources to children and returning schools to places of learning instead of functioning as satellite police precincts.